An Ordinary Day

By Travis WaltonBuy the book • Next page

Condensed from the book Fire in the Sky

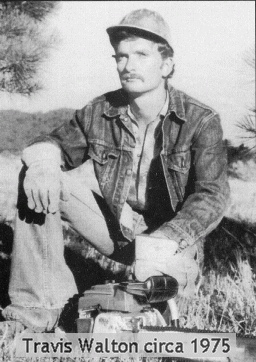

Photo courtesy Michael H. Rogers ©1978

It was the morning of Wednesday, November 5, 1975. To us, the seven men working in Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest, it was an ordinary workday. There was nothing in that sunny fall morning to foreshadow the tremendous fear, shock, and confusion we would be feeling as darkness fell.

We were working on the Turkey Springs tree-thinning contract. Basically, thinning involves spacing and improving the thick stands of smaller trees to allow for their faster growth. That day, November 5, we were cutting a fuel-reduction strip up the crest of a ridge running south through the contract. Fuel reduction is the process of cutting the thinning slash into lengths and piling it up to be burned in the wet season.

The boss, Mike Rogers, was twenty-eight, the oldest of the seven men. He had been bidding these thinning contracts from the Forest Service for nine years. That had been long enough to learn (the hard way) all the tricky pitfalls of the business. He was getting to where he could fairly consistently gauge the price per acre that would underbid the other contractors and still allow a profit margin. Turkey Springs was the best contract, profitwise, Mike had ever been awarded. In fact, it paid the highest acre-price he had ever received.

When we are piling, some of the men run saws while the others pile. I was running a saw, as were Allen Dalis and John Goulette. Dwayne Smith, Kenneth Peterson, and Steve Pierce were piling behind the cutters as we worked our way up the strip.

Dwayne Smith wasn't aware of it, but I had to be constantly careful to fell my trees so as to miss him. His inexperience, or maybe over eagerness, was causing him to work too close to me, instead of allowing a little accumulation of slash to put some distance between us. But at least he was trying.

I could not say the same for Steve. I could see Mike far back down the strip, restacking some sloppy piles to bring them up to specification. Steve took advantage of the boss's absence to rest his can momentarily on a handy log. He was ordinarily a good worker, but was a little disgruntled today because Mike had blamed him for some bad piles Dwayne had made.

I was trying to keep my distance from the other men, but we were coming together on a thick place to one side of the piling strip. The noise of my own saw is loud enough, even with earplugs, without revving all three of them in one spot. Just then I saw a shadow and jumped barely in time to escape a falling tree. I looked to see who had cut it. Allen. His mocking grin let me know it was no accident. I didn't let on that he had needled me. I moved farther up the strip to work. Allen always cut like a crazy man. He was a faster sawyer than anyone out there, even me. His speed helped acre-production, but it kept him from being up to working every day. His uncontrollable temper was probably what made him saw like that, taking his anger out on the trees. Allen had nearly come to blows with almost everyone on the crew, including me. He had a way of picking fights he never finished. Although our differences were forgotten as far as I was concerned, and we were friendly on the job, I suspected that Allen might have one or two lingering bad feelings toward me.

The afternoon sun was starting to cool as it began angling steeper down in the west. In the mountains, sundown comes early. It gets dark very quickly when old Sol slips behind the trees and out of sight behind the high ridges. The gathering chill was beginning to numb my nose. With summer ending, it was starting to get down to five or ten degrees at night. I worked a little faster to ward off the chill, eagerly anticipating the reprieve of the day's conclusion. Not long to go before we could head for home.

Sunset had been fifteen minutes earlier, but we kept cutting in the waning light. I checked my watch again. It was six o'clock at last! Mike was still down the hill a little way, picking up and repiling. I yelled and took the liberty of giving the stop-work signal. The sound of the saws died; the final echoes absorbed into the deepening dusk.

We loaded the chainsaws and gas and oil cans into the back of the '65 International. After arranging the gas cans so they would not tip over and leak on the bumps, Mike slammed the tailgate tightly. The decrepit pickup groaned on its tired old suspension as everyone piled in. There was Dwayne by the left rear door, John and Steve in the middle, and Allen by the right rear door. In the front, I sat by the door, riding shotgun. Ken sat in the middle, and of course Mike was driving. The seven of us usually sat in the same place every day. Nonsmokers in front, smokers in back.

Mike started the old pickup and we climbed north up the ridge toward the Rim Road. It was 6:10. Barring any breakdowns, we should be home before 7:30. We left the windows down so we could cool off some. We were still warm from laboring, in spite of the evening air. Mike, Ken, and I do not smoke and we prefer to inhale genuine, unadulterated air. The four in the backseat lit up as soon as we were in the truck, eager after hours without a cigarette. The fresh air coming in my window was bracing. We usually nap on the way to work every morning, but none of us ever feels drowsy on the way back to town. The rousing activity on the job hones a keenness that stays with us all the way home.

Bouncing over the water-bars in the road — humps of dirt that prevent the road from washing out in the rainy season — the truck kept bottoming out on its springs with a dull clunking sound. The fellows started cracking jokes about the pickup.

Just then my eye was caught by a light coming through the trees on the right, a hundred yards ahead. I idly assumed that the glow was the sun going down in the west. Then it occurred to me that the sun had set half an hour ago. Curious, I thought it might be the light of some hunters camped there — headlights or maybe a fire. Some of the guys must have caught sight of it too, because the men on the right side of the truck had fallen silent.

As we continued driving up the road toward the brightness, we passed in sight of it for an instant. We barely got a glimpse through gnarled branches before we rolled past the opening in the trees.

"Son of a . . ." Allen started.

"What the hell was that?" I asked.

My eyes strained to make sense of the glimmering through the dense stand of trees blocking our vision. From my open window, I could see the yellowish brilliance washing across our path onto the road another forty yards ahead. Intrigued, I was impatient to get past the intervening pines.

From the driver's seat, Mike could not look up with the proper angle without leaning way over, "What do you guys see?" he demanded curiously.

Dwayne answered, "I don't know — but it looked like a crashed plane hanging in a tree!"

Finally, our growing excitement spurred Mike into wringing out what little speed the pickup could still achieve on the incline. We rolled past the intervening evergreen thicket to where we could have an unobstructed view of the source of the strange radiance. Suddenly we were electrified by the most awesome, incredible sight we had seen in our entire lives.

"Stop!" John cried out. "Stop the truck!"

As the truck skidded to a dusty halt in the rocky road, I threw open the door for a clearer view of the dazzling sight.

"My God!" Allen yelled. "It's a flying saucer!"

Buy the book • Go to next page.

Copyright ©1999-2026 by Travis Walton. All rights reserved.